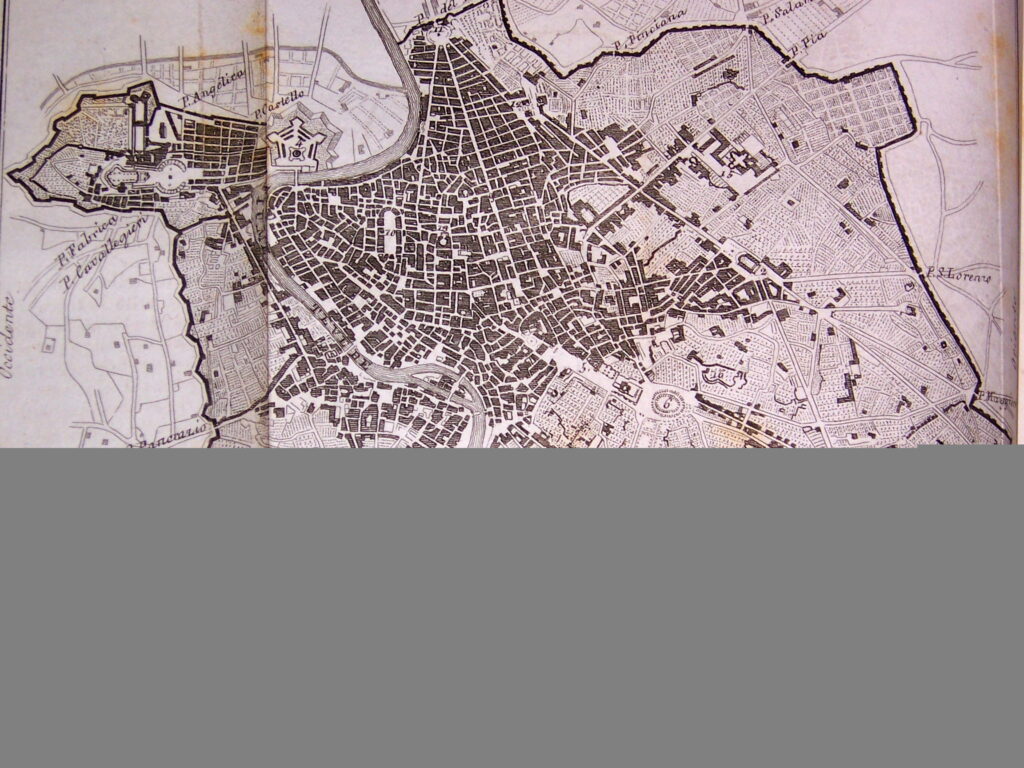

Rome

The founder of the Society of Jesus, Ignatius Loyola (1491-1556), desired to be a pilgrim or a missionary. Instead he found himself working as the leader and chief administrator of a religious order that soon stretched around the globe. Given that the Jesuits had sworn loyalty to the head of the Catholic Church, regardless of who was the pope at the time, it was logical that Ignatius thus spent his remaining years at the heart of the universal church, in Rome. Not only was Rome the center of church activity, and thus important in an administrative sense, it also contained the earliest and some of the most significant Jesuit institutions.

Over time, these institutions included the famous Jesuit churches, the Gèsu and the Sant’Ignazio, and the Roman College, which was founded in 1551. Jesuits from around Europe would study here with some of the pre-eminent Jesuit scholars of their time – including Christopher Clavius and, later, Athanasius Kircher. The Jesuits who graduated from here and then went around the world as missionaries often stayed in touch with their teachers, and were obliged to stay in communication with the administrative leaders of the Society anyway. Their communications rapidly made their way into publications, as collated letters or as books.

Since the Society was an international body ever since its inception, the manner in which these reports were published reveals the rise and fall of printing houses in different parts of Europe as Jesuits living in Rome had connections in cities all over the continent. Thus, as examples, some of Clavius’ work was published in Rome but also in Venice, the first edition of Ricci’s journal was sent away to Augsburg in southern Germany and Kircher published the majority of his works with publishers in Amsterdam.

Jesuit procurators representing their various mission regions also traveled back to Rome and thus the Society maintained its connections with its men throughout the world in a physical sense as well. Rome indeed operated as the heart of their enterprise.

Related Items

Descartes described Athanasius Kircher, S.J. (1602-1680) as “more quicksalver than savant”, others “the premodern root of postmodern thinking.” Kircher also collated writings about China.

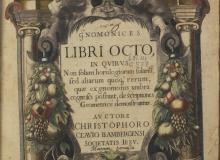

Translation of Euclidean geometry into Chinese

Ricci and his fellow Jesuits relied on their learning, including mathematical principles, especially as they had been taught these by Jesuits like Clavius.